Journeys

Shel asks me why I’m so quiet all of a sudden. How can I tell him that we are too close to Aunt Sal’s, and I have nothing else to say?

Besides, I’m still no closer to making a decision about the grant.

Grant, grant, grant, grant, grant. The goddamn grant. In the past few days, I almost slipped up about the grant, but I know it’s best to keep quiet about it. What good would it do? Shel, the big time shrink, would never close up his practice for a year to go gallivanting around France while I paint indulgent self-portraits. His work is everything, it’s what defines him. Without prestige and the trappings that go with his title, Shel is just another scared little boy who wants his female figure around.

So if I go, I go alone. And if I go alone, he’ll divorce me on general principle. I think he has this fear that if I go away, I won’t come back. He might be right, and I’m not yet ready to face that possibility.

I’m more confused than ever, so what’s the point of saying anything else?

*

As we hit the periphery of town, I notice that Sioux City seems scruffy and low rent, its age lines cutting deeper into the texture of my youth. Even the auditorium looks run down now, the parking lot warped and cracked, crabgrass and weeds pushing through the concrete.

Was it like this last year?

The building looks like an overgrown yellow-brick hull now, the old curved vent pipes on the roof rusting out. But when I was in high school, the auditorium was the place to be, especially when the Caravan of Stars hit town with headliners like Chad and Jeremy, Gerry and the Pacemakers, Herman’s Hermits, Freddy and the Dreamers, Gary Lewis and the Playboys, and Peter and Gordon.

I could sing then–pubescent screams drowned out my voice, so no one could hear how awful I sounded.

And I’d belt out lyrics like “So Ferry ‘cross the Mersey!” and no one would notice or even care how awful I sounded, my voice alternating between a squeak and a crack.

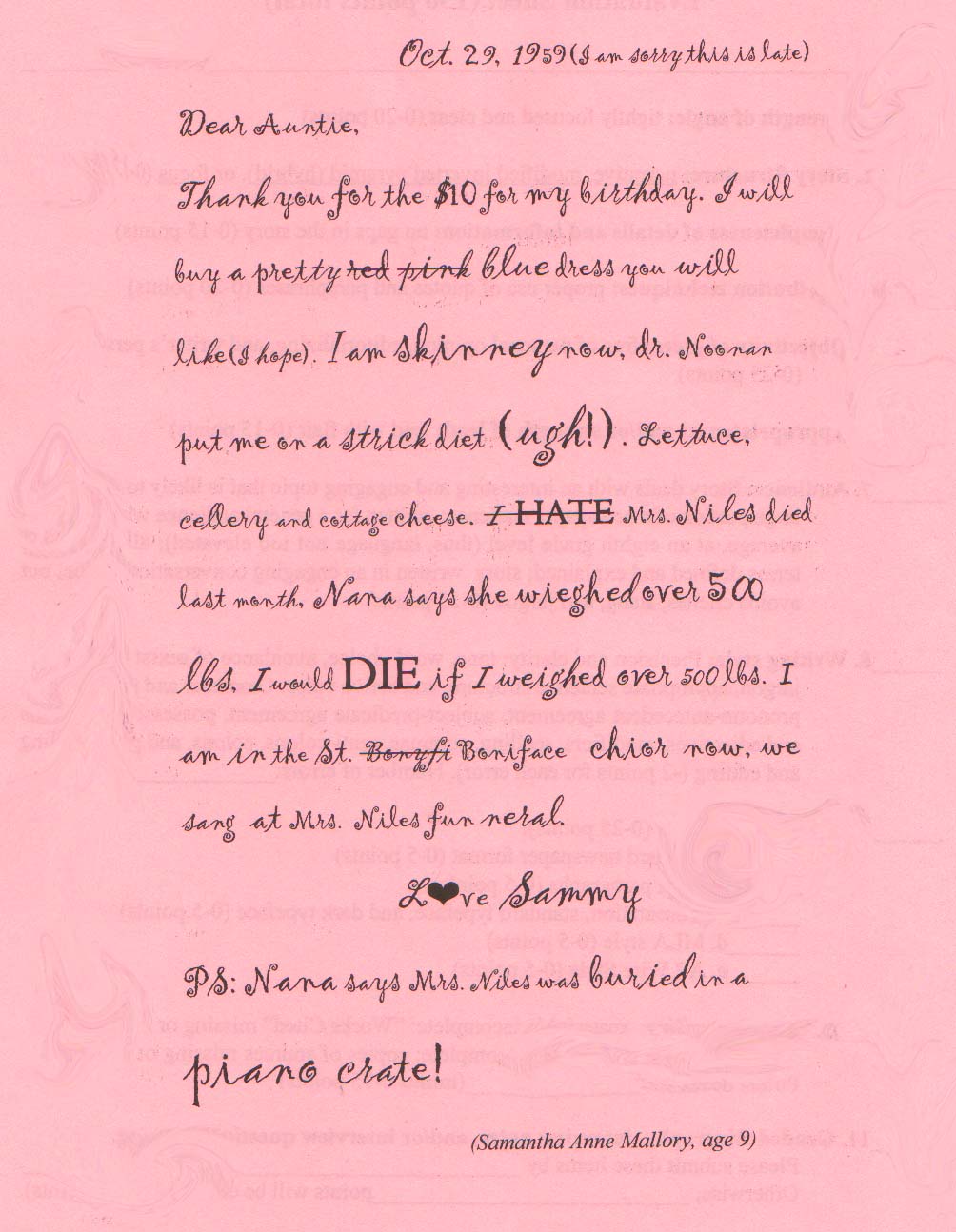

Even before that, I remember our sixth grade choir–wearing red beanies, white blouses with red scarves, black skirts–belting out “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” under the hot lights of KVTV Channel 9. And the auditorium would be filled with our families and friends, even though it was a school day.

But now it looks as though nothing much goes on in there anymore.

*

As we approach the Hamilton Boulevard exit, I think about Nicole at the Circle of Love compound, waiting for her baby’s birth.

My first grandchild.

I wonder if she’s excited or scared. Maybe both.

I’ll never forget the day Nicole was born, how strange it felt when she slid out of my body, wet and slippery. Like she’d been suctioned out by a vacuum cleaner. It all happened so fast, no pain. The pain would come later.

And then I held her, this child with black hair and red skin. Blue eyes those first few weeks. That’s one thing Doug could never take away from me–the moment Nikki and I became mother and daughter. But what has happened since then? Am I really so awful as a mother?

I almost tell Shel to pull over at the Amoco Station on Hamilton and West 8th so that I can call Nikki and tell her to come to Sioux City after all. That I miss her and want her here.

Nana. I know how Nana would react, the things she would say to me when she’d see Nikki’s belly and no wedding ring.

We pass by the station and turn onto West 14th Street.

No comments:

Post a Comment